An

open letter to Bunkai researchers

An open letter to Bunkai researchers

|

| This is what people are unknowingly basing their Bunkai on |

And now, for something completely different...

The following is presented to help

dispel certain myths concerning the Kata of Karate, in an effort to get back to

what Bunkai should be intended for: The study and understanding of the

transmission of fighting knowledge via classical Kata, as it was intended to be

understood. I argue that what we mostly

have today are people trying instead to glorify themselves as really clever

guys by coming up with complex, stylized, and unlikely explanations for the

various movements of Kata.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying

that there aren’t movements that are unclear or unknown; I’m saying that they

do however, have a meaning. And just one

meaning. It is not open to

interpretation. It is open to

misinterpretation.

Once the term Karate is introduced,

everyone seems to throw common sense and critical thinking away. Here is why anyone that thinks Kata have

hundreds of interpretations is wrong.

1. Why would a Kata have hundreds of

interpretations?

This falls apart in every way once you

examine it. How would you ever create a Kata

if every movement could be hundreds of other things? If you are an ancient martial artist creating

a Kata, you are trying to preserve something specific. Let’s apply knowledge of other things to

this. Martial Arts can be considered

like a language, and it is often referred to in this sense. As such, techniques are the alphabet, and Kata

the words. Imagine trying to write a

book if every letter of the alphabet could be any other letter of the

alphabet!?!?!

How would you write “apple?” If “apple” were a Kata, books and internet forums would look like this: “I love ‘apple’ it’s a great way to use the letters q-u-u-h-t”, while someone else says: “me too, it’s my favorite Kata. It teaches how to use e-x-x-m-z.” It doesn’t work like that. A is A. Furthermore, if we don’t agree on what an apple is, no matter how it is spelled, we have written something that can never be communicated, which is the entire point of writing it in the first place. Words are a reference to something. If I ask for an apple and you give me a rock, we have a misunderstanding in our language. If I am going through the trouble of writing something, it stands to reason I want it read and understood. At the end of this essay, it is not my intent for you to walk away thinking “that article could mean anything...” Why would a Karate master of the past do that with Kata? Kata by definition is intended to transmit knowledge. If every movement could be hundreds of techniques, there would be one Kata with one movement! The writing of Kata may be hard to discern, but it still has intentional meaning.

How would you write “apple?” If “apple” were a Kata, books and internet forums would look like this: “I love ‘apple’ it’s a great way to use the letters q-u-u-h-t”, while someone else says: “me too, it’s my favorite Kata. It teaches how to use e-x-x-m-z.” It doesn’t work like that. A is A. Furthermore, if we don’t agree on what an apple is, no matter how it is spelled, we have written something that can never be communicated, which is the entire point of writing it in the first place. Words are a reference to something. If I ask for an apple and you give me a rock, we have a misunderstanding in our language. If I am going through the trouble of writing something, it stands to reason I want it read and understood. At the end of this essay, it is not my intent for you to walk away thinking “that article could mean anything...” Why would a Karate master of the past do that with Kata? Kata by definition is intended to transmit knowledge. If every movement could be hundreds of techniques, there would be one Kata with one movement! The writing of Kata may be hard to discern, but it still has intentional meaning.

2. And why would you hope it did?

You could absolutely never learn a Kata in any

meaningful way. If every movement can be

many other movements, you have just introduced crippling choice. Now I have to decide what this first movement

is, which in turn changes my options for the next move. Once you look at the problems of decision

making when given too many choices, none of which are wrong, you see that this

is not an appropriate way to teach or transmit knowledge.

If you change the first movement, each

subsequent movement is altered to adjust to this new interpretation. It is endless! Imagine a multiple choice test where every

answer is correct. This is clearly not

the way we would want Kata to be. And

who are you to assume you know better than the creator of the Kata? So why DO you want Kata to be like this?

|

| Yes, there are two paths you can go by, but in the long run, there's still time to change the road you're on. And it makes me wonder. |

3. Enter Mr. Miyagi.

It is my opinion that all of this started with

The Karate Kid  . Nothing has influenced modern Karate more

than this movie. While it was one of the

reasons I became a Karate student, it was also the reason a lot of unscrupulous

and unqualified people became Karate instructors. There also came an expectation of what a

sensei should be like, and how he should teach.

In short, for all of you that are looking for these ridiculous and

complicated “A-HA” moments in Kata -that only YOU can figure out- all boils

down to: “wax-on/wax-off.” You are

dreaming of the moment when these seemingly boring and obvious exercises your

sensei made you learn and repeat endlessly suddenly come together and bestow

this magical skill upon you. I do agree that ‘wax on’ is a metaphor for Kata

training (and the real message is not that you need to decipher secrets, but

that you need to train Kata to the point of exhaustion to develop muscle memory

and power), but you aren’t Daniel-san.

. Nothing has influenced modern Karate more

than this movie. While it was one of the

reasons I became a Karate student, it was also the reason a lot of unscrupulous

and unqualified people became Karate instructors. There also came an expectation of what a

sensei should be like, and how he should teach.

In short, for all of you that are looking for these ridiculous and

complicated “A-HA” moments in Kata -that only YOU can figure out- all boils

down to: “wax-on/wax-off.” You are

dreaming of the moment when these seemingly boring and obvious exercises your

sensei made you learn and repeat endlessly suddenly come together and bestow

this magical skill upon you. I do agree that ‘wax on’ is a metaphor for Kata

training (and the real message is not that you need to decipher secrets, but

that you need to train Kata to the point of exhaustion to develop muscle memory

and power), but you aren’t Daniel-san.

In the movie, Daniel doesn’t know any technique. Miyagi had him wax a car over and over

again. Later, he revealed that it was

basic technique, and developing the muscles needed for it. Now when called upon, Daniel had the proper

muscle memory to react. That is Kata. Miyagi was transferring a circle block to him

without trying to explain it, while simultaneously training that technique to

be immediate and powerful. The movie

didn’t continue on with Daniel then adapting that into simultaneous palm

strikes to the temples, or a complex throwing technique, or pressure point

strikes, or wrist grab releases; all using the same motion. Those are all ways one could make use of the

motion of “wax on/wax off”, but it absolutely is not what “wax on/wax off” was intended

to teach. Miyagi had a technique to

teach, and ‘wax on’ is the Kata to do it.

‘Paint the fence’ taught something else, and so did ‘sand the floor’;different

Kata, different purpose (not one Kata with multiple explanations!). But like I said, you aren’t Daniel-san. You do know technique. We call it Kihon. There was a time when Kihon was not taught

separately, but only through Kata. Once extracted,

you had useable techniques to practice.

The more you studied and understood the Kata, the more techniques you

were able to extract. This was already done

for us by the masters of the past! It is

common now to practice reverse punches and stances before learning a Kata, but

this was not always the case. In the

past, you learned a Kata and later extracted things like reverse punch and the

stances from the Kata as an innovative way to drill the Kata techniques in

isolation. We, in modern training, see Kata

as a way to showcase techniques we have learned, so the Kata seem simple. “I’ve been practicing front stance and lunge

punch for a month, now I learned a Kata with front stance and lunge punch in

it.”

That makes sense from a certain perspective. For instance, it is not uncommon to learn a few guitar chords, and then look for a song that uses those chords. But early Karate training didn’t happen like that. And not everyone learns guitar like that. A lot of guitarists (especially the ‘old timers’ from the early 1900s-1960s) would want to learn songs, not learn guitar per se, the same way old timers wanted to learn to fight, but not Karate per se. A guitarist trained that way may be able to play almost any song by ear, or improvise flawlessly, and know a great many songs; but he may not be able to say what chord he is playing, just that it’s the chord from the beginning of a certain song. He learned his chords by someone saying: “put your fingers here”. While able to play songs containing that chord, if asked to play a specific chord or sequence, he would be lost. It is out of the context of his training. Original Karate training was a much more immersive experience; you didn’t train to prepare yourself for training as is now the case. And remember, there were no belts, and no curriculum as we think of it.

|

| A-HA!!! |

That makes sense from a certain perspective. For instance, it is not uncommon to learn a few guitar chords, and then look for a song that uses those chords. But early Karate training didn’t happen like that. And not everyone learns guitar like that. A lot of guitarists (especially the ‘old timers’ from the early 1900s-1960s) would want to learn songs, not learn guitar per se, the same way old timers wanted to learn to fight, but not Karate per se. A guitarist trained that way may be able to play almost any song by ear, or improvise flawlessly, and know a great many songs; but he may not be able to say what chord he is playing, just that it’s the chord from the beginning of a certain song. He learned his chords by someone saying: “put your fingers here”. While able to play songs containing that chord, if asked to play a specific chord or sequence, he would be lost. It is out of the context of his training. Original Karate training was a much more immersive experience; you didn’t train to prepare yourself for training as is now the case. And remember, there were no belts, and no curriculum as we think of it.

Now you are asking “why am I practicing Kata then?” And so, you search for more meaning.

To put it another way; you already know the

circle block, so why learn “wax on?” If it was you learning “wax on”, you would

reject the idea that it is a circle block.

It clearly is an escape from a double wrist grab, or a strike to a vital

point, or to entangle the arms when you are on the ground, or it must be a Buddhist

symbol. But it can’t just be a circle block! Yes it can.

Merging our language example with the Karate Kid example, consider the

scene where Daniel is on the boat with Miyagi.

Miyagi says “bow” and Daniel bends at the waist towards him, bowing. Mr. Miyagi quickly corrects him and indicates

that he meant go stand at the bow of the boat.

While these two words sound the same, they have entirely different meanings. Mr. Miyagi doesn’t say, “Oh, that’s also

correct since they do sound the same...” Instead he corrects Daniel for misinterpreting

his intentions. So part of it is that,

as a student wanting a Mr. Miyagi, you are constantly looking for more meaning in

everything. And as an instructor, you

may have felt obligated to provide that experience (because you want to be

Miyagi as much as they want one), and thus started this boom of “Bunkai”.

Worse yet, as an instructor you may have no

idea what the Kata was for, and you just blindly practiced it, as did your

instructor before you, until one day you realized that you had better “Miyagi”

your Kata if you are going to make any money!

Not to mention, you can’t say “I don’t know” to your students. And surely the more complicated and less

obvious your explanation is, the smarter you are. Right?

|

| Practice this alone as a drill, and what does it look like? |

|

| "Throw anchor. Good. Stand bow. Not bow. Bow!" |

4. Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication (Keep it simple stupid).

The idea that the Kata depicts

incredibly complicated, obtuse, difficult to discern and nearly impossible to

accomplish techniques that require exact attacks from a skilled and compliant

partner is simply absurd. For everything

else in the universe (literally, the universe), we apply Occam's Razor, which

favors explanations based on the fewest assumptions.

This is the exact opposite of how you view

your Kata! For any simple movement you

attribute complex and convoluted techniques then invent the correct attack to

make it “work”, thus adding assumptions.

What assumptions?

|

| Nowhere does it specify that you should use mathematical formulas... |

a. That the opponent is attacking you in modern/skilled ways.

For whatever reason, your Bunkai

always seems to be a defense against a Karate attack or some other complex

attack requiring Karate training to even attempt. The block/double block sequence in Naihanchi

Shodan is probably not against an attacker that threw a straight punch followed

by a simultaneous straight punch and kick.

Think it through. If you faced an

opponent in the 1800s that was capable of simultaneously throwing a kick and

reverse punch (on opposite sides, no less) they must have trained in Karate to

do so. We know that Naihanchi was the

most fundamental Kata in Okinawa at the time (before the Pinan took its

place). We also know that training at

that time was Kata training. What that

means is if your opponent has trained enough to be able to perform the

kick/punch combination, then it stands to reason your opponent knows Naihanchi

Shodan also. It becomes circular.

You wouldn’t think to attack like that unless

you thought that’s what the Kata defended against. Then, you wouldn’t use that attack, because

everyone knows how to defend against it. Why would he attack with a technique

that is amongst the ones every beginning Karateka of the time knew how to

defend (The same motion appears in other Kata, even those of Goju)? Granted, he’s hoping that he isn’t

attacking a Karateka... This leads to the next point, which in itself is another

point of complete misunderstanding by modern Karateka.

|

| It is a fine drill, but is this situation a real concern?? Bunkai problems aren't new to our generation of Karateka. |

b. Karate

ni sente nashi/There is no first attack in Karate.

This is entirely misunderstood by many, and

only partially understood by some. While

I do agree that reading it to mean that you should use your Karate only for defense

is a good start, I don’t think that is necessarily useful, or informative.

This is entirely misunderstood by many, and

only partially understood by some. While

I do agree that reading it to mean that you should use your Karate only for defense

is a good start, I don’t think that is necessarily useful, or informative.

c. That

the Kata is one continuous (sometimes based on a real incident) fight.

That there are multiple attackers (8

directions=8 attackers)/that your opponent will just stand there.

These are very closely related and

absurd. It would not only be impossible

to create a form that duplicated a real fight, it would only have been useful

if you trained that Kata before the fight ever happened. And, it would be utterly useless after that fight

or to anyone other than the version of you before you had the fight. So, unless the old masters were also time

travelers, that’s just not useful. They

wouldn’t spend time on something that isn’t useful. It can vary well contain techniques or

sequences learned in combat, but don’t take it literally to mean it is a

dramatic recreation of an actual fight as it happened. Likewise, it is not constructed to defend

against multiple attackers, unless there was a fad amongst criminals to

position themselves around a victim in specific patterns, and then attack only

when one has been defeated (however it is perfectly fine to think of the Kata

as having multiple mini-fights.

Imagining you are performing attacks and defenses against one opponent/group

at a time and then starting a new sequence with another opponent is perfectly

sensible, but to imagine the Kata is preparing you to fight 8 people in those specific

sequences is silly). When one technique

reaches its conclusion in the Kata, the Kata moves on to another technique you

need to learn. It is far simpler and

more believable to assume that the Kata is trying to transfer techniques that

are useful in general applications.

Speaking of application...

|

| When you finish with my friend completely, I'm totally going to come at you with a lunge punch! |

d. That

there are various interpretations for each movement.

This is a big one. This is the crux of our discussion,

really. This is probably the source of

modern Karateka’s (myself included) misunderstanding about Kata practice. The point here is not that you are free to

interpret every movement however you’d like.

The point is not that each motion can be viewed as a different

technique, but rather, that each motion is a specific technique that can then

be applied differently.

Consider how

Aikido and Jujutsu would teach their techniques. Kotegaeshi is one of the most important techniques

in those arts and one typically learns how to apply it in response to an

opponent grabbing your wrist. You can

apply kotegaeshi in an infinite number of ways (trapping a punch, lapel grab,

against an armed opponent, etc.). The

practice of kotegaeshi from the standard wrist grab is considered the

“classical” form, or sometimes it is even considered “Kata”. The point here is yes, the techniques learned

in Kata are applicable to many situations.

That is to say, that for every technique you extract, there are infinite

ways to use it. That is not to say that

there are many separate techniques implied by the same motion in a Kata. Learning kotegaeshi from a wrist grab doesn’t

also teach uchi mata!

This is a

substantial and important distinction, which I feel should be obvious.

|

| Kotegaeshi demonstrated in Aikido |

|

| A super-sweet UchiMata/Reversal/Badassness!! |

e. That there are secret techniques in the Kata.

Like I

discussed before, there seems to be a desire for some mystical technique or

sequence to appear in Kata and bestow upon you magical powers. Don’t misunderstand. I do not pretend that I know what every

movement in every Kata is trying to convey.

Neither do you. But what I do

know, is that whatever it is, I’ve seen it before and practiced it against a

makiwara and probably a partner (and so have you!), and if not, then it really

is Jujutsu techniques in disguise. Therefore, they are just Jujutsu techniques

that are not in disguise in Jujutsu!

None of it is going to make you suddenly shoot laser beams from your

eyes. Even if you are right about your

complicated Bunkai that incorporates MMA and Kung Fu movie choreography, your Bunkai

is still made up of techniques you already knew. Are the techniques in Kata sometimes

difficult to find? Yes. Do you already know those techniques

anyway? Yes. There are no secret techniques. It is all about learning to apply what you

know, not trying to have more to know.

|

| If you believe things are disguised in Kata, do you think there are multiple people behind a single pair of Groucho glasses? While it could be anyone; it cannot be more than one... |

5.

Star Wars Special Edition Kata.

Essentially those of you looking for,

or rather creating, these “Bunkai” are doing to Kata what Lucas did to the

original Star Wars movies in recent years.

You have some strange desire to go back to something old and add things

that are new, or even worse, to re-imagine the truth. You are basically trying

to rewrite history.

Just because the 14 year olds coming to your dojo because of UFC matches expect ground fighting, doesn’t mean suddenly Naihanchi was invented by the Gracie’s and is secretly hiding strategies for cage fighting (and I’ve seen Bunkai suggesting Naihanchi Shodan was for ground fighting on your back). Just because someone wishes something is in a Kata, doesn’t mean it is (and that doesn’t mean that you can’t apply Naihanchi on your back; just don’t tell me that is what the Kata is for.). Don’t let your Kata become “based on a true story”; or worse “inspired by true events”.

Just because the 14 year olds coming to your dojo because of UFC matches expect ground fighting, doesn’t mean suddenly Naihanchi was invented by the Gracie’s and is secretly hiding strategies for cage fighting (and I’ve seen Bunkai suggesting Naihanchi Shodan was for ground fighting on your back). Just because someone wishes something is in a Kata, doesn’t mean it is (and that doesn’t mean that you can’t apply Naihanchi on your back; just don’t tell me that is what the Kata is for.). Don’t let your Kata become “based on a true story”; or worse “inspired by true events”.

6.

You seem to think that the Kata you perform is its original version.

This is absolutely not true in most cases, and

probably not true in the remaining cases.

For example, if you practice Shotokan, don’t bother studying the Bunkai

of your Kata in an attempt to understand original intent. Your Kata is documented and proven to not be

the same as it was on Okinawa (it’s not even the same as the first changes Funakoshi  himself made). While much is similar, it

is not exact, and where changes are made the original intent is completely

lost. It is the equivalent of redubbing

the dialogue in the rowboat scene in Karate Kid to have Mr. Miyagi say “stern”

instead of “bow”. They are both parts of

a boat, but not only is the double entendre missing, so is the value in the

lesson about balance (the stern is far more stable). I’m not just singling out Shotokan

either.

himself made). While much is similar, it

is not exact, and where changes are made the original intent is completely

lost. It is the equivalent of redubbing

the dialogue in the rowboat scene in Karate Kid to have Mr. Miyagi say “stern”

instead of “bow”. They are both parts of

a boat, but not only is the double entendre missing, so is the value in the

lesson about balance (the stern is far more stable). I’m not just singling out Shotokan

either.

This is true of all of

the Kata regardless of lineage. Shotokan

Kata just happens to be, without question, different than it historically

was. You can argue the Kata is better; you

cannot argue that it is not different.

And, this should all be about deciphering what teachings the Kata truly

contain. I’m of the personal opinion

that this sadly can never be fully known, as even Choki Motobu mentions that

certain Kata are no longer as they used to be practiced (he mentions that

strikes that used to be hiraken are now seiken, etc.). He also says that

different teachers had differing interpretations even then-- leading to

different versions and misinterpretation as early as our records can be traced,

by the earliest masters we can name.

These differences are important to understanding the Kata. Motobu mentions for instance that Itosu used

to emphasize dropping the foot in the “Naihanchi kick”, while others emphasized

the lifting of the foot. This means one Kata

is a sweep, and the other is a kick or stomp.

mentions that

certain Kata are no longer as they used to be practiced (he mentions that

strikes that used to be hiraken are now seiken, etc.). He also says that

different teachers had differing interpretations even then-- leading to

different versions and misinterpretation as early as our records can be traced,

by the earliest masters we can name.

These differences are important to understanding the Kata. Motobu mentions for instance that Itosu used

to emphasize dropping the foot in the “Naihanchi kick”, while others emphasized

the lifting of the foot. This means one Kata

is a sweep, and the other is a kick or stomp.

That affects the preceding and subsequent techniques significantly (or

at least our understanding of them). One

of those is correct, and the other is a misunderstanding (or both are

completely wrong!). It is interesting to

note here, that Funakoshi himself said that changing the Kata was common

practice that should and will continue. Furthermore, I’ve had Okinawan Masters

tell me that the meaning of some postures are absolutely nothing more than

formal introductions/salutations, a preparatory posture (Kamae), or a

chambering technique. Itosu himself

indicated that he felt certain movements were “just for show”. Are they?

|

| Out with the old... |

|

| In with the new... |

7.

They could be just for show.

This is hard to accept, and every Bunkai

expert will tell you that there are no wasted movements in Kata. Why? Itosu

clearly never said that--quite the opposite.

So where did it come from? It

seems to just be a rule that people coming up with modern Bunkai created to

justify their Bunkai. If you have ever

seen Okinawan dance, you would recognize certain similarities between their

dance and their Kata. Since there is

simply no documentation to directly contradict the idea that they are

connected, I cannot rule it out (though, like you, I also hope that I’m not

learning dance moves…).

One can imagine

that it would be convenient and easier to connect the techniques in a Kata

using popular dance moves as a mnemonic device, as well as to add enjoyment to

the practice, and even to add secrecy (It could also be that certain movements

in Kata are intended to make it seem like you are practicing a dance if

accidentally observed practicing in secrecy.

Who knows?). This is no different

than the “alphabet song” we teach our children, which is really the melody of “Twinkle

Twinkle Little Star”. We took a song

that was easy to remember and popular for children to sing, and changed the

words to teach something specific. And

then added a relatively meaningless line concluding, “Next time won’t you sing

with me...” simply because there was ‘leftover’ melody at the end of the song. It is irrelevant to the teachings. It is just for show. A thousand years from now, imagine there

being no record of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” ever existing-- what would the

future scholars think of the “Alphabet song?”

Why that melody? Why that ending

to the song?

The answer is clear to us, and unknowable to them: It is just for show. Consider a future where only Weird Al Yankovic ’s recordings of songs

exist, and not the original versions; would they still be parody songs?

’s recordings of songs

exist, and not the original versions; would they still be parody songs?

|

| Bet they look pretty similar when they're practicing... |

|

| Another One Rides the Bus actually makes more sense, in a story telling way, than the song that inspired it... |

The answer is clear to us, and unknowable to them: It is just for show. Consider a future where only Weird Al Yankovic

8.

The Internet is not a reference.

While many references can be found on

the internet, just because someone said something on the internet doesn’t mean

it is true or valid. Just because you

cite what someone said on the internet, it doesn’t make them right (or

you). All of this talk of modern Bunkai

is purely speculative, at best. This is

potentially true even of the original masters, for the Kata they learned was

almost definitely not the same as it was in China just a generation before

them. So often these same opinions found

on the internet are cited as fact, and then used to justify your opinion-based

interpretation of Kata. Here are some

examples:

Closed

hands mean you are grabbing something

It might sometimes.

Does that mean always? Also consider that we have been told by many

of the old masters that the Kata were mostly open handed until they were

changed by the Okinawans to use the more prevalent Okinawan Te punches. Consider Uechi Sanchin in comparison to Goju Sanchin.

|

| Kanbun Uechi, Sanchin. |

There are no blocks in Kata

|

| Gogen Yamaguchi, Sanchin. |

|

| This is arguably the first mention of the Gracies in America! |

|

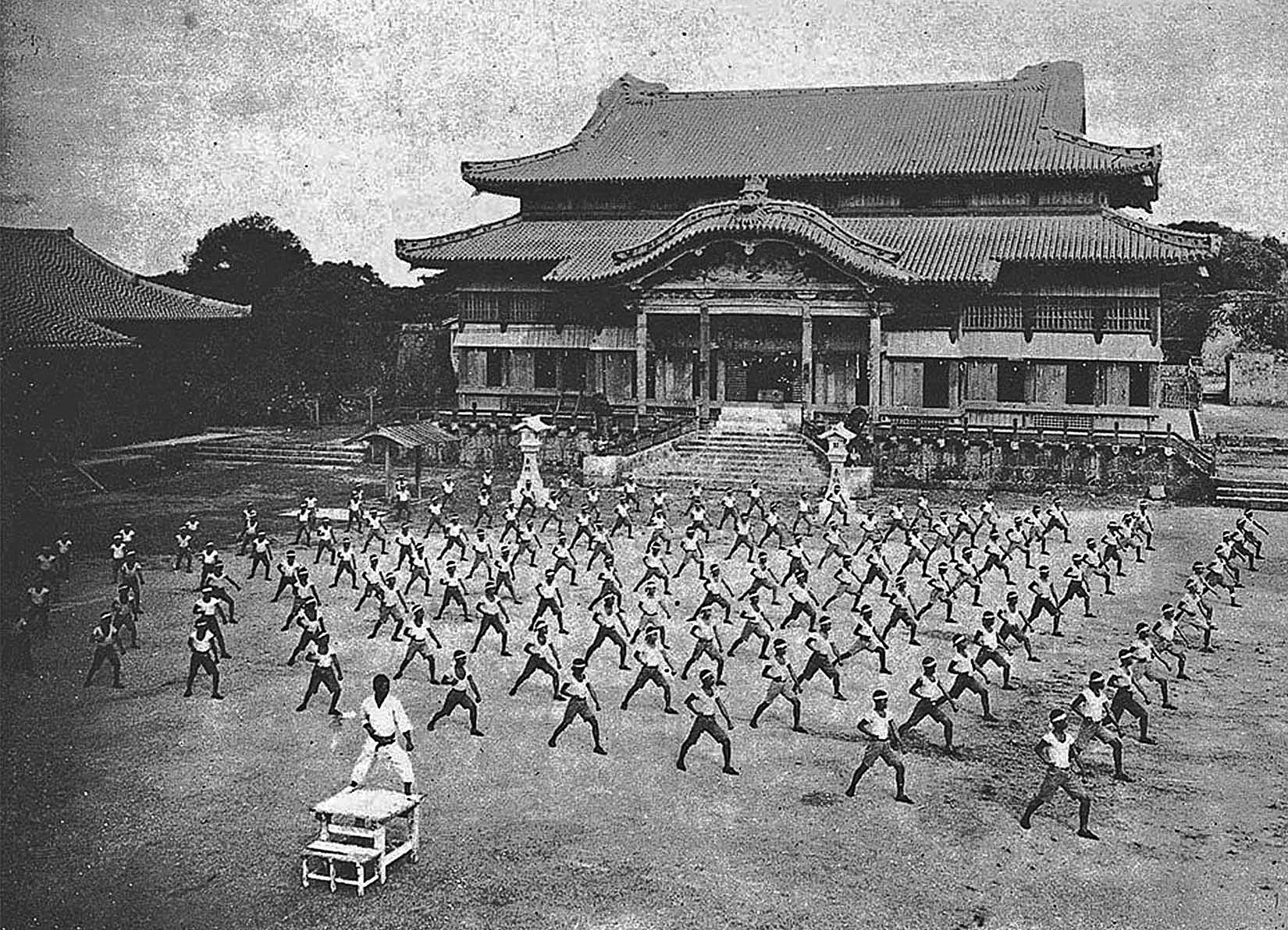

| Itosu (center) with Kendo practicioners at the Okinawan School |

Additionally, there is the argument

that there are no blocks in Kata because they are all strikes. This isn’t entirely false, but this is a

combination of two errors of training, mostly apparent in sport Karate

training. The first error in training is

not practicing the full spectrum of strikes, focusing almost exclusively on

reverse punch. Original, traditional Karate

has always been clear that the same techniques can be used as a block or strike

and, when blocking, one should do so as if striking the attacking arm/leg. So there is nothing new or interesting in

saying that you can strike with a knife hand block; that’s called a knife hand

strike. But to suggest that one always

ignore an attack and instead charge in with an attack of your own is less than

good advice. By focusing your training

only on punching, combined with this need to find “hidden” things in Kata, I

can understand how you can think that knife hand blocks and palm heel blocks

are concealed strikes, but if you practice and drill those techniques as

strikes already, they aren’t concealed!

The second error of training which helps to breed and perpetuate this

kind of thinking is not practicing full contact Bogu Kumite. I believe it quickly becomes apparent that

blocking is the most important skill to master when you start getting punched

in the face and groin repeatedly and quickly. Of course timing, positioning and Tai Sabaki

are also incredibly important, as is striking.

But make no mistake; you want to block the opponent’s attack whenever

possible. This also does not rule out

simultaneously striking and blocking, nor does it rule out striking while

blocking, or blocking with a strike, or striking with a block, or striking with

the blocking hand, or blocking with one hand and striking with the other etc.

|

| Bogu Kumite in action! |

Another thing to remember is that you

are not defending against another Karateka in Kata (as we covered

earlier). You are preparing to defend

against real life or death attacks on the street. An opponent on the street may attack you with

bare hands, but it is more likely that they will have a weapon. You want to know how to block if you are

attacked with a weapon. And it is

reasonable to assume much of Kata is preparing you for defense against an armed

assailant. And it may very well be a

skilled armed attacker, as weapon arts predate (and were originally separate from) Karate on Okinawa, including Bo, Sai, Sword, etc.

In fact some Kata are argued to be

derived or adapted to be empty handed simply to disguise that they were weapon Kata. Practicing weapon Kata with a weapon would be

seen as practicing with a weapon.

Practicing empty handed would seem like dance.

George Mattson once told a story about

seeing a very old man practicing what seemed to be a familiar Kata being

performed with Sai. When he asked his

teacher about this, he replied “yes this is the original way”. Maybe times when “open hand strikes” seem to

grip oddly and transform to "closed hand strikes” one is really just

spinning the Sai from tip to butt? And bizarre double hand techniques are

because of a Bo? We often hear of making the hands like swords or spears, and

we call it knife hand, we don’t call knives “sharp hands”. The point being, Martial arts are often based

on observation of animals’ natural weapons, then adapting those movements. Man, having no natural weapon of his own,

built them. It makes sense then, that

study of Man’s weapons is the study of weapons.

It could be that much like some Chinese Kata reflect adaptation of

animal fighting movements, some Okinawan Kata may reflect the adaptation of

weapon techniques (human fighting movements) for times when there are no

weapons. Spear hand for times when one

would extend the Sai, or Tunfa; and the fist for times when one would retract a

Sai, or Tunfa. And, like Chinese

reference to animals in naming, the Okinawans are using weapons in naming

(sword arm, knife hand, spear hand). Now

motions where one hand is seen to be too short to be a strike take on a

different meaning with an extended Sai in that hand (attacking), and a

retracted Sai in the lead hand (defending). I cannot endorse or refute this idea. But it is an idea.

|

| I'm not sure if she is applying weapons to Naihanchi, or if we are adapting Sai Kata for empty hands... |

|

| Seems like he thinks it's a block... |

Additionally, some argue that the

“rising block” has to be a strike because it doesn’t make sense to block a

straight punch to the face with it; so it has to be a strike. Isn’t it more reasonable then, to say that

maybe you aren’t blocking a straight punch to the face? Perhaps you are deflecting an overhead club

attack (or perhaps your opponent is significantly taller than you, in which

case, it is feasible, but an untrained opponent isn’t likely to use a straight

“Karate” punch as we discussed before...).

If there is no such thing as a “rising block”, then Karate leaves you

completely defenseless against an overhead attack? That doesn’t seem reasonable to me.

|

| Him too... |

|

| For Kung Fu practicioners, sure looks a bit like Pinan Shodan, no? |

|

| The true Bunkai of Pinan Shodan, or coincidence? |

The

names of the techniques mean nothing

This one is closely related to the

above, and stems from the idea that just because we call it a block that

doesn’t mean it is a block and that it was never called a block until it was

taught in schools during the early 1900s.

First of all, that is highly questionable, and I’ve never seen any

citation to support that assertion (other than quoting other people’s opinions

from the internet). We have texts from

many masters who learned Karate before its introduction to schools and they

also refer to blocks and strikes.

The argument tends to say that because of having to shift from private to group instruction the need to name techniques arose. If that was the case, it still doesn’t matter. Let’s assume that Itosu never used any terms to refer to anything at all (nor did any other master, whether before him or his contemporary [and regardless of lineage]). That still doesn’t matter, because eventually, for whatever reason, he did use terms. This brings us back to the point about language earlier in the article. We discussed words being a reference to a specific referent. Rocks existed before we devised the word “Rock”. It is not the case that rocks sprang into existence when we came up with the word. Likewise, while in this example Itosu never used words to describe the techniques, he clearly thought of them in a certain way. In other words, he called them blocks because that’s what they already were and that’s what he already considered them to be. Another less important point to remember here is that much of Karate was imported and adapted from Chinese methods, and we know that the techniques were named in poetic, but somewhat descriptive ways. While it may be true that the Okinawan masters renamed the techniques, it is hard to believe that they would “un-name” them! And if they completely invented the techniques themselves, they never gave them names? There is literally nothing that doesn’t have a name; the first thing people do when creating something or discovering something is naming it. And unlike the Chinese poetic naming convention, the Okinawan’s chose a scientific and direct naming convention instead of continuing with the mystical type theme. Something to consider is that if you are right about some of these outlandish ideas and complicated Bunkai; that means you no longer practice Karate, and that you have to see Karate as a bunch of people dancing to choreography from the 1800s, throwing silly punches and kicks, instead of doing what tend to look like Aikido demonstrations as most Bunkai does. You must think that all of Karate is based on the complete and total misunderstanding by every founding Master of Karate, including those that trained in China and started “Karate” as we know it. So don’t say you practice Karate.

The argument tends to say that because of having to shift from private to group instruction the need to name techniques arose. If that was the case, it still doesn’t matter. Let’s assume that Itosu never used any terms to refer to anything at all (nor did any other master, whether before him or his contemporary [and regardless of lineage]). That still doesn’t matter, because eventually, for whatever reason, he did use terms. This brings us back to the point about language earlier in the article. We discussed words being a reference to a specific referent. Rocks existed before we devised the word “Rock”. It is not the case that rocks sprang into existence when we came up with the word. Likewise, while in this example Itosu never used words to describe the techniques, he clearly thought of them in a certain way. In other words, he called them blocks because that’s what they already were and that’s what he already considered them to be. Another less important point to remember here is that much of Karate was imported and adapted from Chinese methods, and we know that the techniques were named in poetic, but somewhat descriptive ways. While it may be true that the Okinawan masters renamed the techniques, it is hard to believe that they would “un-name” them! And if they completely invented the techniques themselves, they never gave them names? There is literally nothing that doesn’t have a name; the first thing people do when creating something or discovering something is naming it. And unlike the Chinese poetic naming convention, the Okinawan’s chose a scientific and direct naming convention instead of continuing with the mystical type theme. Something to consider is that if you are right about some of these outlandish ideas and complicated Bunkai; that means you no longer practice Karate, and that you have to see Karate as a bunch of people dancing to choreography from the 1800s, throwing silly punches and kicks, instead of doing what tend to look like Aikido demonstrations as most Bunkai does. You must think that all of Karate is based on the complete and total misunderstanding by every founding Master of Karate, including those that trained in China and started “Karate” as we know it. So don’t say you practice Karate.

|

| Using Age Uke as a strike... |

|

| Doesn't look like a "secret" to use your elbows... |

Meanings

of the movements were deliberately obscured for children

The argument here is that when it was

taught to school children it was in order to raise a stronger, better,

more-prepared army by teaching them martial arts. So, naturally, they removed all of the

“deadly” techniques, and focused on physical fitness!?!? I think that is absurd. Again, there is absolutely no documentation

of this, other than people saying it on the internet. And it doesn’t make any sense. There are far better ways to condition

children without going through the immense effort and time requirements of

learning Karate (not to mention the effort and time in teaching Karate to

them). Hanashiro was a gymnastics

teacher at the school, as well as a martial artist. If regimented exercise was all that was

needed, he could’ve easily come up with something more like “cardio kick

boxing”, “Tae Bo”, or even Yoga, while still instilling respect and

discipline. Why would you want to remove

the actual martial content of Karate when preparing soldiers? Not to mention that Itosu also sought to

popularize Karate, removing its efficacy would be counterproductive in

promoting Karate as the ultimate martial art.

Wouldn’t it be easier then, for Itosu to simply teach the punches and

kicks and just not teach Kata at all rather than change and create Kata to take

the Karate out? Everyone also has this

vision of it being 5 year-olds running around doing Kata. Keep in mind that we are also talking about

the equivalent of high school students.

In our school system do high school wrestlers learn fake wrestling? And, remember that in Japan at the time, it

was a conscripted Army requiring that all men starting at age 17 serve in the

military for several years (even in America at the turn of the 20th century

teens would be considered adults. Most

people were working, married, and had families by 18. In fact, around 1900 the age of consent in

the US ranged from 10-13). Does it make

sense that you would, in preparing them for the military (which they would all

enter), condition and train them in fake Karate for years, only to have to try

to retrain them once they joined the army in the course of a few weeks? Or does it make more sense to begin the

military training as early and fully as possible? And for what it’s worth, Musashi was 13 when

he defeated his first opponent by beating him to death with a staff.

|

| Itosu's dream, realized. If you think the martial techniques have been removed from our Kata, this is the only true Bunkai! |

Furthermore, people argue that the

unified group practice of Kata performed by commands was also to prepare for

military training. While that is similar

to military formations and group training, I believe it is a symptom, not an

aim of the training. Karate was never

practiced that way before being taught in school, so that is not an element of Karate

training being brought into the schools, that is an element of school training

(or military training) being brought into Karate. Training of any kind, including school

studies, was incredibly harsh and strict at that time. If anything was affected by bringing Karate

into the schools, it was how it would

later be taught (mostly in Japan, which also incorporated more of Kendo and Judo

formalities), not what was taught.

Another point to consider here is that

the Pinan Kata are Itosu’s legacy. Even

in his time Itosu was considered a famous martial artist and teacher. Why would he want to be remembered for

creating Kata that contain “watered-down” or “dance” Karate?

He was trying to popularize an art that he

dedicated his life to, and trained incredibly hard to master, only to turn

around and make a mockery of it by turning it into meaningless aerobics

exercise? Would a classically trained

pianist who spent their lifetime learning the works of Mozart and Chopin

suddenly open a music school that taught its students to just bang on the keys

of the piano randomly and aimlessly?

That’s absurd. Yabu Kentsu was

once quoted as saying “If you have time to practice the Pinan, practice Kusanku

instead.” This is a fine position to

take; if you know Kusanku and/or other classical Kata! I believe this is the point of the Pinan Kata:

To transfer the knowledge of all of the various classical Kata (that Itosu

knew) into Kata that progressed in a logical order and were simpler to teach but

provided a wider overview of Karate. In

other words, what Itosu did was create a progressive curriculum of Karate. The name “Peaceful Mind” as Pinan is often

translated has been interpreted to mean that after learning those Kata one can

rest at ease knowing they can defend themselves. I think it goes slightly further to mean

“...without learning any other Kata”. He

took the best parts (as he saw it) from the Kata and put them together in a progressive

manner. I think his intent was quite the

opposite of what Yabu said. Instead of

the Pinan being useless if you knew Kusanku, Itosu thought all the other Kata

were superseded by his Pinan! Remember,

the people learning the Pinan Kata were often (not exclusively) school students

that were not specifically Karate students.

If the only Kata they would ever learn was what they were taught in

school, those Kata (the Pinan) had better cover the full spectrum of the

classical Kata. A far cry from watered

down Kata, they are condensed Kata!

|

| This isn't what it looked like when taught in backyards... |

|

| A prerequisite for most fitness programs thanks to Itosu. |

What

attacks are we REALLY defending against?

As I mentioned, wrestling and

grappling (and Sumo) were well-known on Okinawa, and practiced there. Karate and western boxing were not

commonplace on Okinawa or Japan at the time.

So, what would Kata actually be useful for? Since Jujutsu, or at least Judo, was well

established before 1900, it doesn’t make sense to be making Kata to hide Jujutsu

techniques. At the time they were literally

the most well-known techniques in the world.

There were Jujutsu books published in English from the same time that Itosu was creating the Pinan, so it is safe to assume there were Japanese books prior to that, in addition to the obvious direct exposure. Again, I agree some movements are certainly throws or locks (and escapes), but many people want to insist that Kata are almost entirely Jujutsu-like and that somehow that indicates a higher level of both their understanding of the Kata and of actual technique. In other words, as a beginner it’s fine to have blocks and strikes, but as one matures, he should see that there are no blocks and strikes; they’re all throws and flowing joint manipulations.

In my opinion, Karate directly rose to prominence as a means of defeating grapplers, not a way to become one. Let’s think about things for a moment. In the late 1800s and early 1900s on Okinawa, what are you training for? Two main points of view emerge, one is the viewpoint of the warrior class having to defend the King (it is well documented that many martial arts masters of the day were actually high ranking public officials), and the other is of a person concerned about personal safety, beyond military engagement. Let’s for a moment consider the military use of Kata as a training aide. We know that there was definitely Chinese military training on Okinawa, which may be a source of some Kata.

So if the Kata have a military usage, they are absolutely not intended to defend against a punch or other Karate style attack. It stands to reason you would be training against an opponent with a weapon. War has never been fought empty handed! This means Kata are either engineered to be used with a weapon against a weapon, or empty handed against a weapon. The possibility of two unarmed combatants fighting to the death seems too far-fetched to be a universal training concern. It is completely untrue that Karate was created by farmers defending themselves; we know that the original practitioners were royal employees. As a soldier in war, it is clear what your personal protection goals are, but, as a person seeking self-defense in everyday life, what are your concerns? Well, as a frequently (as in absolutely always) conquered nation, your first concern is fighting trained soldiers that are occupying your country. Putting things in perspective, remember that while Okinawa was trying to popularize Karate, they were also being taken over by Japan. Relations were not excellent between Okinawa and Japan at the time. Choki Motobu, for example, refused to learn Japanese and could only teach in mainland Japan through translators. As a result, he was deemed illiterate and brash, even though he was of high social standing with royal lineage! It is reasonable that as a citizen you may be concerned about self-protection from Japanese invaders. If Karate is intended to protect the Okinawans from the Japanese, wouldn’t it stand to reason that Okinawan Karate techniques and Kata are intended to defend against Japanese arts like Jujutsu? Japan took Okinawa as a prefecture three years after the formation of Judo. It is for this reason that I submit that early Kata were intended to defend against weapons and/or Jujutsu; you would either be attacked by an untrained opponent, or one trained in Jujutsu. In my early years of training, under sensei that trained in the 50s and 60s, you learned and were tested on Kihon, Kata, Kumite, and Self-Defense.

The

“self-defense” techniques were nothing more than Kata sequences applied to a

partner. And almost EVERY self-defense

was a defense against a grab or hold.

You would defend against wrist grabs, hair grabs, lapel grabs, chokes,

bear hugs, etc. Unfortunately, Bunkai in

recent years has supplanted this type of “self-defense” training. It seems to me that in the past it was

obvious that Karate was seen as a system to defeat grappling, and these partner

self-defense drills demonstrated that.

“Self-defense” sequences were taught and trained and tested with great

emphasis, and in many ways were more Bunkai than Bunkai. The real basis for the success of grappling

in MMA, in my opinion, is the rules. In

a competitive situation, when you are grabbed, you have to grapple. In a life

and death situation, grappling is the last thing you would want to do. It is an immense expenditure of energy, and

if you aren’t a grappler primarily, you will be defeated.

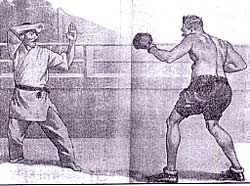

A famous example to help illustrate this idea, I think, is Choki Motobu defeating the Boxer in Japan. I am a huge fan of Choki Motobu, but I don’t think the victory was as much a personal victory as it was a “style” victory. The Russian boxer was attempting to make a name by defeating Japanese Judoka; he certainly was not expecting a “striker”. Choki Motobu knew that he could not reveal what he was going to do until he studied his opponent for a round. During that match, just like every other challenger before him, Motobu wore a Judo gi. The boxer incorrectly assumed that he need be prepared to defend against a grappler. Accounts differ as to what Motobu actually did, but it was a strike-based attack by all accounts. Motobu did not box the Boxer. He did not win a Boxing match. He used Karate against a Boxer expecting a Judoka. He didn’t employ all those grappling techniques and ground fighting skills that you think are the aim of Kata; he struck him, and more importantly, in unexpected ways (even if he was expecting Motobu to box with him, he still wouldn’t have expected Karate strikes or possibly even the locations of the strikes).

If they charge you around the waist, you

cannot gouge their eyes out, or pop their ear drums, or elbow the top of the

spine with a downward strike, when you’re in a mount you cannot grab and twist

testicles, or bite, or spit, etc. Karate

is designed with the idea of brutal efficacy immediately in response to the

threat of grappling, seeing grappling as a no win situation; especially since

we are told by the masters of the past that Karate is for fighting multiple

opponents that are ruffians, and villains.

There were Jujutsu books published in English from the same time that Itosu was creating the Pinan, so it is safe to assume there were Japanese books prior to that, in addition to the obvious direct exposure. Again, I agree some movements are certainly throws or locks (and escapes), but many people want to insist that Kata are almost entirely Jujutsu-like and that somehow that indicates a higher level of both their understanding of the Kata and of actual technique. In other words, as a beginner it’s fine to have blocks and strikes, but as one matures, he should see that there are no blocks and strikes; they’re all throws and flowing joint manipulations.

In my opinion, Karate directly rose to prominence as a means of defeating grapplers, not a way to become one. Let’s think about things for a moment. In the late 1800s and early 1900s on Okinawa, what are you training for? Two main points of view emerge, one is the viewpoint of the warrior class having to defend the King (it is well documented that many martial arts masters of the day were actually high ranking public officials), and the other is of a person concerned about personal safety, beyond military engagement. Let’s for a moment consider the military use of Kata as a training aide. We know that there was definitely Chinese military training on Okinawa, which may be a source of some Kata.

So if the Kata have a military usage, they are absolutely not intended to defend against a punch or other Karate style attack. It stands to reason you would be training against an opponent with a weapon. War has never been fought empty handed! This means Kata are either engineered to be used with a weapon against a weapon, or empty handed against a weapon. The possibility of two unarmed combatants fighting to the death seems too far-fetched to be a universal training concern. It is completely untrue that Karate was created by farmers defending themselves; we know that the original practitioners were royal employees. As a soldier in war, it is clear what your personal protection goals are, but, as a person seeking self-defense in everyday life, what are your concerns? Well, as a frequently (as in absolutely always) conquered nation, your first concern is fighting trained soldiers that are occupying your country. Putting things in perspective, remember that while Okinawa was trying to popularize Karate, they were also being taken over by Japan. Relations were not excellent between Okinawa and Japan at the time. Choki Motobu, for example, refused to learn Japanese and could only teach in mainland Japan through translators. As a result, he was deemed illiterate and brash, even though he was of high social standing with royal lineage! It is reasonable that as a citizen you may be concerned about self-protection from Japanese invaders. If Karate is intended to protect the Okinawans from the Japanese, wouldn’t it stand to reason that Okinawan Karate techniques and Kata are intended to defend against Japanese arts like Jujutsu? Japan took Okinawa as a prefecture three years after the formation of Judo. It is for this reason that I submit that early Kata were intended to defend against weapons and/or Jujutsu; you would either be attacked by an untrained opponent, or one trained in Jujutsu. In my early years of training, under sensei that trained in the 50s and 60s, you learned and were tested on Kihon, Kata, Kumite, and Self-Defense.

|

| Motobu had the same idea. Analyzing the Kata as usable self-defence against attacks that were commonplace at the time. |

A famous example to help illustrate this idea, I think, is Choki Motobu defeating the Boxer in Japan. I am a huge fan of Choki Motobu, but I don’t think the victory was as much a personal victory as it was a “style” victory. The Russian boxer was attempting to make a name by defeating Japanese Judoka; he certainly was not expecting a “striker”. Choki Motobu knew that he could not reveal what he was going to do until he studied his opponent for a round. During that match, just like every other challenger before him, Motobu wore a Judo gi. The boxer incorrectly assumed that he need be prepared to defend against a grappler. Accounts differ as to what Motobu actually did, but it was a strike-based attack by all accounts. Motobu did not box the Boxer. He did not win a Boxing match. He used Karate against a Boxer expecting a Judoka. He didn’t employ all those grappling techniques and ground fighting skills that you think are the aim of Kata; he struck him, and more importantly, in unexpected ways (even if he was expecting Motobu to box with him, he still wouldn’t have expected Karate strikes or possibly even the locations of the strikes).

|

| Motobu's opponent in the ring. |

It used to be that Karate was regarded

as the most complete fighting system, though that opinion has faded in recent

years. I think the reason that it should

again be considered the most complete is that the Kata of Karate prepare you to

use its special striking and blocking methods (unknown outside of Karate), in

conjunction with your prior exposure to Jujutsu/Sumo/Wrestling-type holds and

grips; to protect you against all other known forms of attack, including

Jujutsu/Judo, Sumo, Western Boxing and Wrestling methods of the day, as well as

the weapons (Kobudo) of the day; all of which were very well known at the time and,

at the very least, were widely written about subjects even if direct exposure

didn’t occur. And additionally, Kata

must train against the completely untrained violent criminal of the day and

their known methods of attack. We assume an untrained person will throw a

“haymaker” punch at us, or grab our wrist; there must have been assumptions

concerning what an untrained person would think to do at the time of the Kata’s

creation.

I think it’s safe to say Karate

masters of the day would agree with the idea of “do not let yourself have a Jujutsu

technique applied to you fully, and do not initially use Jujutsu techniques as

your strategy, though they may be a means towards such strategy, as in counter

measures against a Jujutsu technique”. I

think that is a reasonable assumption to use in analyzing Kata.

The whole point of this writing is not

to say “Stop analyzing our Kata”; quite the opposite. What I am suggesting is that we all work

together collaboratively in searching for the most reasonable explanation of

what teachings the Kata truly contain, rather than continuing this trend of

self-marketing. Everyone wants to

promote themselves as a great master with such complex explanations of the Kata

that they should be celebrated as discovering the secret. When the “secrets” have been discovered, they

should seem obvious and simple once explained.

There should be nearly unanimous cries of “that has to be right, that makes total sense”; at which point the Bunkai

world should cease coming up with alternatives.

Once Einstein said “E=mc2”, Physicists said “Oh… yup, that

makes sense; done.” Much of this Bunkai

is like you saying “yeah… well, F=mc2”, in hopes of acknowledgement,

and revealing a lack of understanding at the same time.You are no better than your students, you have simply trained longer. Everyone wants to put on a Red Belt and play Superman. This has to stop. When people thought the Solar System circled the Earth, they worked out incredibly complicated theories and models to demonstrate that they were right. Once that view was proven incorrect, the real explanation, and models showing the movement, became much simpler. The Masters that brought Karate to light through their writings and teachings always sought to demystify the Martial Arts. From the very beginning, Itosu himself makes note that it is separate from Buddhism and Confucianism in his Ten Precepts. The early English-Language writers also took great measure to demystify the Arts as well. It wasn’t until comic book ads that the mystification started creeping back in, only to be fully realized in the Kung Fu movies of the 60s and 70s (and TV and Media in general for that matter). This was not in our Arts originally. A student of the martial arts had no idea about these mystical themes from his training; and the public had no idea that it wasn’t part of the Arts from their lack of training. Not until the public, perhaps due to their misconceptions, began actual training. This had two effects. First, they began to have some of their misconceptions ripped away, in a good way. But also in a bad way, affecting retention- they want to try to take the pebble from your hand. Which leads to the second reason; it also had the effect of changing the training so that those misconceptions weren’t entirely stripped away, grasshopper.

|

| All modern Karate lineages can trace their origin back to the original Sensei; Television. |

Thank you for taking the time to

consider my attempt at, not providing the answers, but rather trying to find

the right questions to unlock the teachings of the past. Seek what others have sought, not what they

have found.

NOTES:

From the Sept. 1989 Playboy article:

“Rorion (pronounced Horion, in the

Portuguese way) is a master of a kind of no-holds-barred jujitsu practiced by

his family in Brazil for 60 years. Gracie jujitsu is a bouillabaisse of the

other martial arts: Judo (throws), Karate (kicks, punches), aikido (twists),

boxing (punches) and wrestling (grappling, holds). Its primary purpose is

defensive; i.e., to render attackers immobile. Rorion believes that since most

real fights end up on the ground 90 percent of the time, Gracie jujitsu is the

most devastating of all martial arts, because it relies on a series of

intricate wrestling-like moves that are most effective when the combatants are

on the ground. All a jujitsu master must do is avoid his attacker's kicks,

punches and stabs until he can throw him to the ground and then apply either a

choke hold to render him unconscious or a hold in which he can break his

attacker's arm, leg, back or neck. A jujitsu fight is like a chess match, in

that the winner is usually the one who can think the most moves ahead of his

opponent.”

Furthermore, in 1987

Ashida Kim (who will be discussed in a future post), in Deadly Grip of the Ninja wrote: “In the Koga Ryu, grappling

techniques are taught first. This is

because most fights quickly deteriorate into wrestling contests where grappling

is primary. It is felt that the Ninja should not only be qualified in this

field, but also highly competent."

.JPG)

Very good article. And I though I was alone! Almost point for point, you summarized what I think about kata applications and the modern quest for 'bunkai'. That there is one meaning for each technique, not 'infinite bunkai' etc.etc.

ReplyDeleteGood work!

However, there is one point where I do not agree with you. Namely, that you cannot learn from kata anything you did not already know. This is not true. I learned some new and surprising techniques by studying kata!

In fact, this is how you know you are on the right track - when you actually learn something new from the kata, instead of just rehashing what you already knew. Then you know somebody is teaching you....

(Of course, the new technique must be a good one, not some BS.)

Even thought your article is a voice of reason, I feel the need to add one thing:

ReplyDeleteActually, there is couple of reasons why looking for the original meaning - the 'one application' - of kata will never be popular. I am not sure you realize that.

I)First, of course, because many people are mentally incapable of the task. (meaning,lacking the necessary intelligence, knowledge, rationality,imagination etc.)

II)Second, there are people who actively profit from the 'infinite bunkai' fiction; from the fact that the real meaning is not known.

Who are these people?

1)The masters itself.

The 'infinite bunkais' fiction allows the martial arts masters to feed their students BS for YEARS based on the same technique. It is the same with Omote/Ura/whatever bunkai:

"Yeah, the omote bunkai I just taught you is crap, but wait until you see the Ura! Of course, you must study another five years before I show you..."

This ignorant teaching model allows martial arts teachers to make up more and more stories, that they, like modern Shaherazads, tell their students to keep them coming another day..and another etc.

Or to cite another fable, 'infinite bunkai' is like a bag with infinite amount gold: You can take a new bunkai out of it everyday, and your students are going to pay for it over and over.

Paying either in money, or with status and respect.

Look at the clowns, how knowing they appear when they smugly announce: "Okay, of course this movement can be this..or this...or this...."; while their naive students stare in amazement.

What would happen if the master would have to teach one, definite application for a movement? All this mystery would be lost.

(Have you ever thought that perhaps it were the masters themselves who came up with the 'infinite bunkai' fiction, specificaly for the above reasons?)

2)The martial arts students

The fact that there is supposed to be 'infinite bunkais' for a movement allows every mediocre mind to feel entitled to come up with his own. People do not try to find the meaning because they love truth, or because they want to learn to fight. It is sort of an intellectual passtime; so that they can feel creative in their 'karate training', yet do not have to strain their minds too much.

Admitting there is one application would put a sudden end to most people's 'bunkai creativity'. They are not going to like this.

So,without much exageration, getting rid of the 'infinite bunkai' fiction would criple the entire karate industry.

III) Third, philosophical reason. In current mental climate, people fear anything that is certain, or fixed. It is, of course, irrational fear; but very real, nonetheless. Everything that smells of truth,certainly or univocality is intuitively disliked by majority of people. It is what Chesterton predicted when he wrote in 1920's: "We are on the road to producing a race of men too mentally modest to believe in the multiplication table."

Telling people there is one - just one - true application, true meaning for every movement will make them feel like they are being abused by Gestapo. And they will react accordingly.

------------

The above are reasons why, even if the theory is clearly superior, as you show by your arguments above, search for the true meaning of kata will never be popular - at least until significant climate change.

What advice would I give someone new to martial arts who was thrown off by your questions?

ReplyDeleteTrain with Patrick Mc Carthy.

http://www.koryu-uchinadi.com/

He actually showed us 35 variations of the salutation of Passai/Bassai Dai. All were highly functional and realistic self defence.

I have some books by Ronald Lindsey of Matsumura Seito Shorin Ryu, and high level katas like Gojushiho teach fighting strategy - but not the stuff you see in the Nakayama Kata series describing bunkai.

As for the use of classical (pre traditional) martial arts in the real world - the classical is simply what gracie was going back to, and the high level MMA guys and classical masters have respect for each other - generally Bullshido is not instructive. I have seen hilarious rebuttals of MMA white belts by classical and MMA black belts when the usual "you can't anti grapple" nonsense is brought up. Sure you can anti grapple - and there is a counter to that. A good fight, be it boxing or BJJ, is full of counters. A military commander may simply exchange a long series of counter offensives.

Like it or not, there is (some) grappling in kata, as shown by Mc Carthy and Vince Morris.

What should a new student do? Realise there is value in point fighting (Lyoto Machida), train at all ranges (stand up, grapple, trapping, clinch/takedown) and spar full contact for practice and gradings, learn some quality kata applications (Mc Carthy or Flane Walker from Won Hop loong Chuan) and learn weapons (even proficiency with a Jo, Bo or even a Shillelagh will prepare you well for all weapons, see how Arnis teaches), then they will be a competent and well rounded martial artist.

The best thing to do is cut down on the amount of kata that you do but make it value added. Your theory suppsoes Abernathy is wrong as he has not been taught from the source like Mc Carthy. His stuff works, is congruent with McCarthy's theories and resembles the kata closely.

Another thing to realise is that Matsumura (Shrui te) and the Tomari te masters taught Seisan and Jion respectively with iron fans, hair pins and knucle dusters (Tekko) [would be applicable for a yawara stick as well]. Here in the classical system, the multiplicity of applications arises. In this instance we can be sure of the authenticity.

Just as a boxer can land a left hook from hundreds of situations, and a carpenter can make 1000s of items with a limited toolset, I'm not offended if there is a multiplicity of bunaki, as long as it is realistic, follows the kata in movement and the movements are not awkward and can be easily taught to brown-junior level blackbelts.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteMy first reply got lost so I'll make this even more succinct.

ReplyDeleteI agree with much of your idea but it sounds like your desire to validate your training when many now dismiss those ways, is causing you to draw shaky conclusions. e.g. no one needs a kata to tell them to push away a non threatening drunk, and no one pushes anyone with a rising block.

Don't listen to idiots on the net, instead find those who have done the research so that you can know where the basis of these arguments originates from. You will find that the culture of applying a wide variety of techniques through a small number of kata movements is fully supported by the Okinawan progenitors (such as Chomo Hanashiro in Genwa Nakasone's book or Choki Motobu in his own work) and is further supported by the cultural use of forms in southern Chinese kungfu.

Fighting arts contain fighting techniques. The separation of striking and grappling is an artificial construct of the Japanese adaptation of fighting arts into spiritual pursuits and sports.

Karate did not come from that and old pictures of Funakoshi using kata punches as throws and joint locks ultimately disprove your position.

Sorry to be blunt, but brevity is my main concern now.

I said I liked your idea because like you I believe the simple classic labels provide a very important level of understanding in kata study. I differ though because I know that there is more to it and that the skill building of a multiplicity of variations is preferable to the eternal white-beltdom of Japanese karate's traditional approach.

As I said, get the books, or better still find Abernethy or Morris or McCarthy as they have done the research for you. At least then you will have a more solid understanding of the logic and basis of the approach. Actually being convinced would mean being ready to let go of your old views and that is not for everyone.

Brilliant articles ! This is exactly like what I've been pondering for years, but not articulated like this. Excellent points made.

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting this info. I just want to let you know that I just check out your site and I find it very interesting and informative. I can't wait to read lots of your posts. Best waxing places in Manhattan

ReplyDeleteThe next time When i review an online site, I am hoping which in turn it assists produce me personally additional written content up to this specific location. Spa packages Edmonton

ReplyDeleteThis is an excellent article. I have read it multiple times. Thank you for adding some skepticism to the "hundreds of interpretations" crowd.

ReplyDeleteYour blog provided us with valuable information to work with. Each & every tips of your post are awesome. Shop Aviation Themed Clothing

ReplyDeleteDelightful web blog. Almost everything here's superb. The facts usually are completely mind-blowing! My partner and I would like to examine this information again tomorrow. And also I most certainly will examine it. Movers International Movers

ReplyDeleteGreat post full of useful tips! My site is fairly new and I am also having a hard time getting my readers to leave comments. Analytics shows they are coming to the site but I have a feeling “nobody wants to be first. κορυφαίους τίτλους σήμερα

ReplyDeleteHi, this is a very interesting article and I have enjoyed reading many of the articles and posts contained on the website, keep up the good work and hope to read some more interesting content in the future. I got a lot of useful and significant information. Thank you so much. harga pintu garasi

ReplyDelete